The (Not Always Subtle, But Always Decisive) Difference Between Critical Thinking and a Critical Attitude

Critical thinking is the ability to analyze arguments with rigor. A critical attitude is the willingness to question. The problem is that they don’t always go hand in hand.

We’ve all seen this scene: in a team meeting, someone jumps in right away:“That makes no sense, this won’t work!” Depending on how confidently that person speaks, the rest of the room often goes silent and discouraged.

If we’re lucky, someone has the courage to ask: “But why won’t it work? How did you reach that conclusion?” If the answer is vague, repetitive, or poorly reasoned, the verdict is clear. What we’re seeing is a dangerous mix: an overly sharp critical stance combined with weak critical thinking.

We often confuse the two—but they are not the same.

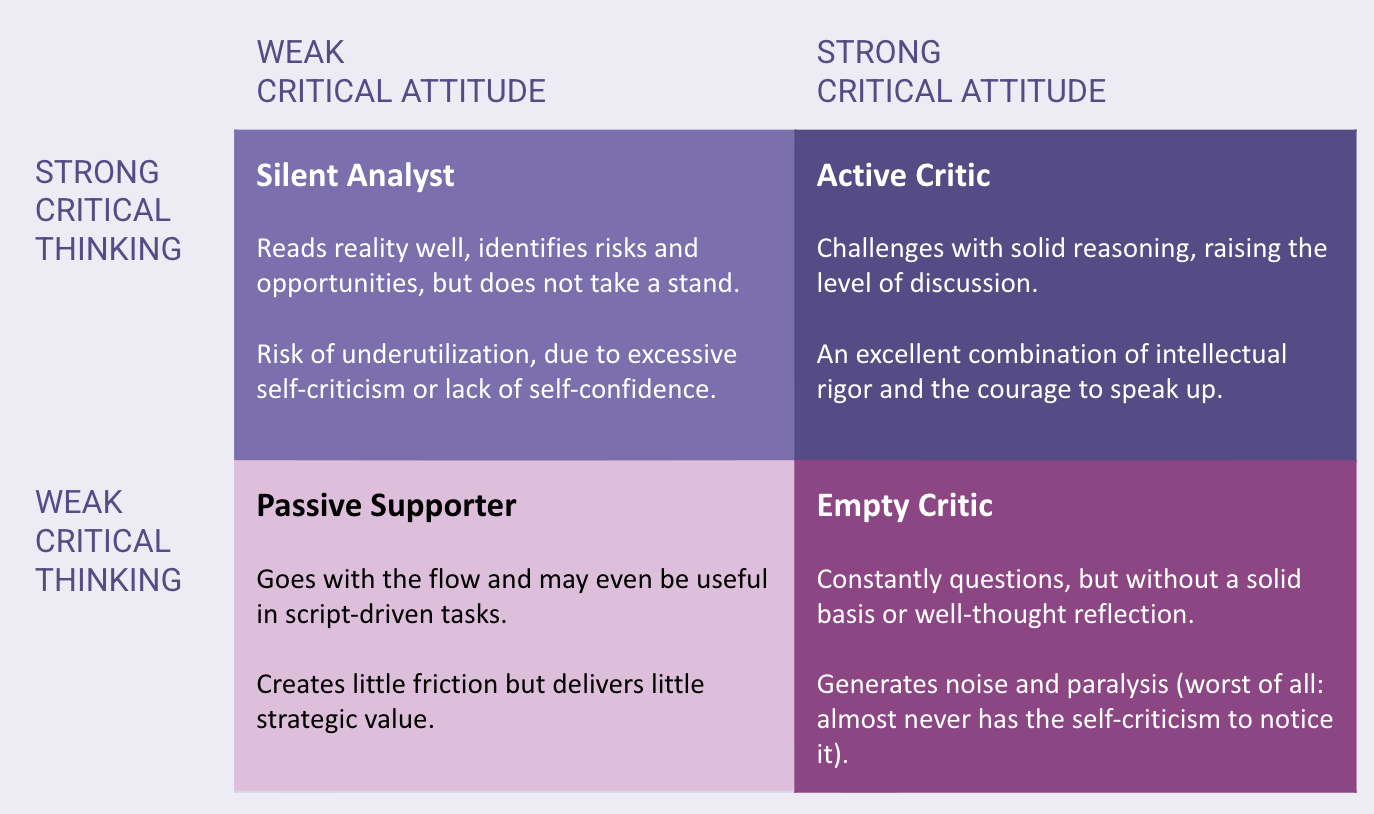

Critical thinking is an intellectual ability: analyzing information, identifying assumptions, weighing arguments. A critical attitude, on the other hand, is a behavioral tendency: the inclination to disagree, challenge, and question.

The best results come when these two dimensions—the cognitive and the social-emotional—work together.

Sometimes it’s the critical attitude that triggers the need to revisit assumptions. Other times, reflection strengthens the willingness to voice disagreement. The problem arises when they don’t “talk” to each other.

Picture these two dimensions crossed, and four quadrants emerge.

Ideally, we want to be “Active Critics.” But it’s not always easy.

Critical thinking can be “lazy”—after all, it requires effort, deliberation, and focus. This is Kahneman’s famous System 2 at work. And as a cognitive skill, it also needs development, which in turn requires measurement and awareness.

Here lies a paradox: people with an exaggerated critical attitude are often less open to spotting flaws in their own perceptions. This creates a vicious cycle: with plenty of criticism but little self-criticism, they challenge every idea except their own assumptions. And by never questioning themselves, they reinforce the sense that “the world is wrong, and my stance is right.”

How the Matrix Helps You Personally

As an individual, you can use this framework to reflect: Am I showing up more as an “Active Critic,” or do I fall into the traps of the “Silent Analyst,” “Passive Supporter,” or—worse—the “Empty Critic”?

A simple checklist can help transform critical attitude into meaningful contribution:

When I challenge an idea, what assumption am I questioning?

What evidence supports my critique—what do I have beyond a “gut feeling”?

If my critique is accepted, what alternatives do I propose?

What would make me change my mind?

Example: instead of saying, “Clients won’t like it,” try this:

Assumption: churn decreases with paywall. Evidence: pilot NPS dropped 6 points in two representative accounts. Alternative: trigger paywall only after 3 uses. Falsification: if NPS ≥-2 and ARPU +5% in 30 days, I’ll support the initiative.

How the Matrix Helps Leaders

For leaders, the caveat is clear: don’t use this as a rigid framework to “label” people. Reality is far more complex. Still, the model helps navigate the territory of critical sense—separating mere contrarian behavior from truly valuable questioning.

From a cultural perspective, here are some practices that make critical thinking visible:

In every challenge, prompt explicit assumptions: “OK, but why?”

Praise team members when they change their mind after encountering stronger evidence.

Document not only decisions but also the reasoning behind them.

If possible, implement a “PEAF Standard of Critique”: Premise, Evidence, Alternative, Falsification.

“But Isn’t Critical Thinking Only for Strategic Roles?”

Not at all. In fact, the only exception might be highly repetitive jobs with little scope for value creation. (And honestly, the problem is that such jobs still exist.)

Even interns or junior analysts can make a big difference with strong critical thinking.

That’s the customer success rep who spots a new kind of complaint early—possibly preventing a major issue. That’s the developer who asks the right questions about a project before writing a single line of code. That’s the marketing analyst who pushes back on an agency, demanding clarity on how numbers in a proposal were calculated.

At SkillCert, we’ve seen in aggregated results that critical thinking doesn’t always accompany strong mathematical reasoning, pattern analysis, or assertiveness.

And in today’s world of widespread AI, it’s hard to imagine a more essential intellectual skill than critical thinking—especially when combined with creativity. But that’s a topic for another post.